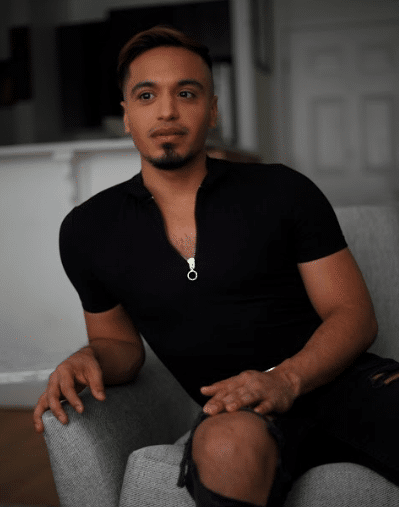

Jose Alfaro at home in Boston, MA, June 2019

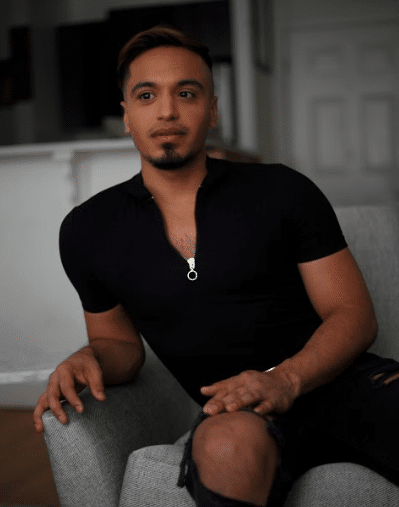

Jose Alfaro at home in Boston, MA, June 2019

Jose Alfaro had nowhere to go.

He couldn’t go home to his family in Navasota, Texas, an outpost of 7,000 people located 70 miles northwest of Houston that was once popular with gamblers and criminals as America expanded westward.

At just 16 years old, Alfaro’s parents had kicked him out for being gay. His father gave him an ultimatum: Go to conversion therapy or walk out the door.

Meanwhile, the much-older man he was seeing at the time had been cheating on him. Alfaro knew that if he went back to the man he simply calls “the 36-year-old,” he would only continue breaking his heart.

The summer before his senior year of high school, Alfaro met a man named Jason Daniel Gandy on the now-defunct hookup website Gay.com. Gandy, who was at that point a total stranger, offered him a third option. He told Alfaro that he had a “nine-bedroom home in Austin, Texas” and that he was willing to help.

“I have so many friends who have gone through what you’ve gone through,” he remembers Gandy telling him. “I just feel really bad for you.”

“At the time, I didn’t feel like I could trust him,” Alfaro tells Queerty. “I had just met him, but I didn’t know what to do. This was my only choice.”

That conversation in the summer of 2007 changed the course of Alfaro’s life. For three months, Gandy trafficked him as a prostitute as part of a massage therapy business he operated out of Gandy’s home. Alfaro was one of several young men victimized by Gandy, who was sentenced to 30 years in a federal prison in Beaumont, Texas, last December.

Gandy’s crimes came to light when he was stopped at London’s Heathrow Airport in 2012 while traveling with a 15-year-old boy. Six years later, Gandy was found guilty of sex trafficking, transportation of child pornography, and transportation of a minor, among other offenses. He is not eligible for parole.

In April, a jury awarded Alfaro, who sued Gandy in a separate civil trial, $1.43 million in damages, nearly a million dollars more than the $485,000 his legal team initially requested. Fish & Richardson, which represented Alfaro in court, noted in a press release that the “large amount of damages awarded [to its client] in this type of case is rare.”

While the ruling may be an extraordinary act of restitution for a survivor of sex trafficking, the experiences that Alfaro describes are anything but rare. Shortly after he moved in, Gandy claimed the teenager would need to make money to earn his keep. He offered Alfaro a job in his business giving “four-hand massages”—meaning two masseurs work the client at the same time—under one condition: He would have to lie about how old he is. If one of their clients asked, he was instructed to say he was 18. The age of consent in Texas is 17.

The first time he gave a client massage, Alfaro realized he would be required to use more of his body than his hands alone. When he walked into the room, the client was nude on the table. At first, he couldn’t help but giggle, thinking the gentleman had misunderstood the instruction to lie under the thin white sheet separating massage therapists from their customers. But soon Gandy, who was to provide the other two hands, was undressing and instructing Alfaro to do the same. That’s when he thought to himself, “OK, this is probably going to be more than just a massage.”

“The guys were allowed to touch me,” Alfaro remembers. “They were allowed to get physical with me. Throughout the weeks and months, it would get worse and worse.”

At first, Alfaro didn’t recognize that what was being done to him was wrong. Because Gandy and their clients were significantly older than he was, he thought they had his best interests in mind. Many of the men who sought out Gandy’s services on Craigslist were married, taking off their wedding rings as they undressed.

But eventually, things got to a point of no return. Shortly before he made the decision to leave, he discovered child pornography on Gandy’s laptop. The revelation wasn’t a surprise. One time when the two were shopping at the grocery store, a young boy walked by who Alfaro claims couldn’t have been more than 11-years-old. He alleges Gandy looked at the boy “almost like he was going to eat this kid.”

That was when Alfaro says he started to realize: “Something is wrong—something is very, very wrong.”

That was when Alfaro says he started to realize: “Something is wrong—something is very, very wrong.”

The last time that Alfaro worked for Gandy, the customer wanted to give him a massage instead. He was willing to pay for it. After Gandy left the room, the client instructed Alfaro to lie down on the massage table and raped him.

“That was when I decided it was time for me to go,” Alfaro says. He went back to “the 36-year-old,” finishing up his studies at an alternative high school in San Antonio while saving up to go off to college the next year. Although Alfaro allowed himself to nurture a fantasy that his unfaithful partner would transform into a superhero who “saved” him from a “monster” who allowed him to be sexually assaulted, he also knew that things wouldn’t change. It was an old conundrum: trying to make the best decision for his health and safety when there were no good options.

But Alfaro says life after sex trafficking was not like his fantasy, a world filled with “rainbows and butterflies.” After leaving his unfaithful partner, he experienced a severe case of post-traumatic stress, starting to use cocaine and ecstasy to cope with the loneliness and anxiety he was feeling. After spending a few semesters at Northwest Vista College and Blinn College—both in Texas—he dropped out because he was too depressed to go to class.

What made him feel especially alone, Alfaro claims, is that few of his friends recognized the severity of what he had been through. Whenever he would attempt to talk to others about his experiences, they would simply nod and say, “That’s crazy.” No one ever told him to go to the police, to call a hotline for survivors, or to seek out a counselor to discuss his trauma. In fact, no one even called it sex trafficking until he confided to an aunt years later what really happened while he was “away.” She told him that young children who “get sold all the time in different countries.”

Before that conversation, Alfaro had begun to doubt his own truth. “I almost felt like I was crazy,” he says, “like I’m making this up, like this isn’t real.”

While society has come to slowly recognize the severity of sex trafficking, one of the difficulties of having others see his experiences for what they were is that queer and transgender survivors are often ignored. In a 2014 report for the U.S. National Institute of Health’s National Library of Medicine, researcher Omar Martinez found that 58.3 percent of LGBTQ homeless youth—or nearly six in 10—“are exploited through sexual prostitution.” That rate is significantly higher than the 33.4 percent of heterosexual and cisgender youth who are forced or coerced into sex work, he says.

“LGBTQ sex trafficking is commonly overlooked and rarely reported by local and national governments,” Martinez claims, pointing to the lingering stigma causing this erasure. “The underreporting of sex trafficking among this population makes it difficult to understand the specific nature of the crimes and the total number of people affected.”

What makes queer youth particularly vulnerable to being targeted by sex traffickers is that—like Alfaro—many simply have nowhere else to turn. Even the resources for sex trafficking survivors are largely created with straight and cisgender people in mind. Many advocacy organizations also fail to distinguish between individuals who are forced into what is effectively sex slavery and others who engage in sex work in order to survive, a critical distinction for a population that is disproportionately likely to live in poverty or be forced onto the streets. Between 20 to 40 percent of homeless youth are estimated to be queer or transgender.

What makes queer youth particularly vulnerable to being targeted by sex traffickers is that—like Alfaro—many simply have nowhere else to turn. Even the resources for sex trafficking survivors are largely created with straight and cisgender people in mind. Many advocacy organizations also fail to distinguish between individuals who are forced into what is effectively sex slavery and others who engage in sex work in order to survive, a critical distinction for a population that is disproportionately likely to live in poverty or be forced onto the streets. Between 20 to 40 percent of homeless youth are estimated to be queer or transgender.

After leaving Gandy and then leaving “the 36-year-old,” Alfaro didn’t immediately stop doing sex work. While he struggled to support himself on his own, he started performing in cam shows online and briefly became a rent boy. For a while, he even started giving massages on his own. When he looks back on this period of his life, he does not feel shame. Instead, he simply wants to get back to who he was before he was trafficked: a “bubbly, confident, happy” kid who loved to sing and dance.

But Alfaro has found contentment on his own terms. He lives in Boston, where he works as a professional hairstylist. In addition to advising the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) on the realities that face LGBTQ victims of sex trafficking, he sits on the board of Gay Sons and Mothers, a community group formed by psychotherapist Rick Miller. True to its name, the organization highlights the “special and complex bond that exists between gay sons and their mothers,” as well as the “disappointment” among LGBTQ people who face family rejection.

While Alfaro doesn’t count himself among the latter group, he says it’s still difficult for his family to face their own guilt over what happened to him, even 12 years later. Alfaro is close with his sisters but says that he only sees his parents “once, sometimes twice” a year because it “hurts them” to see him. But even though their relationship may never be repaired, Gandy says he is ready to forgive them.

“I know that what happened to me wasn’t their fault,” he says. “Parents are not given a pamphlet that tells you what to do.”

Alfaro hopes the recent court victories against Gandy—first in December and then two months ago—will help everyone begin their journey toward healing. Gandy will be personally liable for the damages, and with the settlement, Alfaro plans to write a memoir about what he went through and hopes it inspires other survivors to come forward. He describes the book, tentatively tiled Gay, Crazy, Sane, as part of his “road to recovery.”

“I’m starting to come to a place in my life where I’m realizing that I deserve respect,” Alfaro concludes. “I’m worth a lot more than what I had felt for a long time.”