On a stormy afternoon in November, employees at Grindr’s in-house digital magazine, Into, were on edge. They’d just left an emergency staff meeting at the company’s West Hollywood headquarters where they had been told the LGBTQ news outlet was about to publish one of the most explosive stories in its 15-month history. The topic: a Facebook post in which Scott Chen, the president of the gay dating and hookup app, wrote that marriage should be “between a man and a woman.”

Don’t discuss the story with your Grindr colleagues, editors told Into staff. Relax and do your best to behave normally at lunch. When the building unexpectedly lost power that afternoon, some paranoid employees wondered if Chen was trying to kill the story by cutting the electricity. (The cause was later determined to be a rain-induced blackout.)

Published by three Into staffers from Zinqué, a nearby French bistro, the article — “Grindr President Says Marriage Is ‘Holy Matrimony Between a Man and a Woman’ in Deleted Social Media Post” — sent shockwaves through the company. It was a humiliating black eye for the popular app, one of the most recognizable gay brands in the world, and another gaffe that severely damaged its standing with employees. Within two months, Into’s entire editorial staff was laid off, and by spring, Grindr had shelved plans for an initial public offering, which had been hamstrung by mismanagement and government scrutiny of its Chinese owner.

For Grindr employees, Into’s untimely demise was the culmination of the internal rifts and tactical missteps that continue to afflict the company to this day. Later this year, Grindr is expected to launch another media venture, its second attempt at an LGBTQ-focused site, and prepare its business to be sold. But six former employees who spoke to BuzzFeed News under the condition of anonymity, citing nondisclosure agreements and fear of retaliation, are not so optimistic.

“There was a sequence of unfortunate events that exposed cultural differences, lack of strategic clarity, and internal angst between those who were gay and straight,” said one former employee. “And that’s what Grindr still is today.”

Grindr declined to answer the majority of questions from a list sent by BuzzFeed News about the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) investigation, employee complaints, and internal problems, but in a statement it said that its “significant growth” from 3.3 million to more than 4.5 million daily active users was a sign of its “hard work and cooperative efforts of the entire team.”

“Unfortunately, change can be difficult, and not everyone will agree with our efforts to professionalize Grindr’s operations and improve the user experience,” said a company spokesperson. “As a result, some employees have left, others we have parted with. But throughout, we have listened to our users and our team when making these decisions.”

Many of Grindr’s humbling missteps over the last 18 months can be traced back to the decisions made around its sale to Kunlun Group — a Chinese social gaming company, and the installation of new leadership, namely Chen. According to a number of senior employees who have since left the company, the layoffs and disorder that followed Chen’s ascension hampered Grindr and continue to do so today.

“It’s amazing he was in that role as CTO, much less as president,” one former employee told BuzzFeed News. “He was unprepared to be in charge of a company of that size. Scott didn’t understand the size of the brand, and he was narrowly focused and reckless.”

Just two years earlier, Grindr had been a very different place — a steady and profitable 8-year-old company hoping to shed its image as a cisgender gay men’s hookup app to become an all-encompassing LGBTQ-focused media destination. Into had been a key piece of that vision, a digital magazine executives pitched as a “queer Atlantic.” There was also Grindr for Equality, an advocacy arm intended to “help LGBTQ people around the globe” with sexual health and safety campaigns.

That vision is in tatters now. Chen has refocused Grindr on its core demographic of cis gay men and its main business of facilitating hookups as it grapples with the repercussions of a federal inquiry by CFIUS. Earlier this year, CFIUS — a federal interagency commission that oversees foreign investment in the US — had declared Grindr’s Chinese ownership a national security risk, forcing its parent company to put it up for sale. Kunlun has since pledged to sell it by June 2020.

Even if it does find a new owner, former employees worry Grindr will never be the same.

“In terms of organizational damage that has been incurred, it probably will be irreparable,” one said. “It will be a shadow of itself when that transaction is done.”

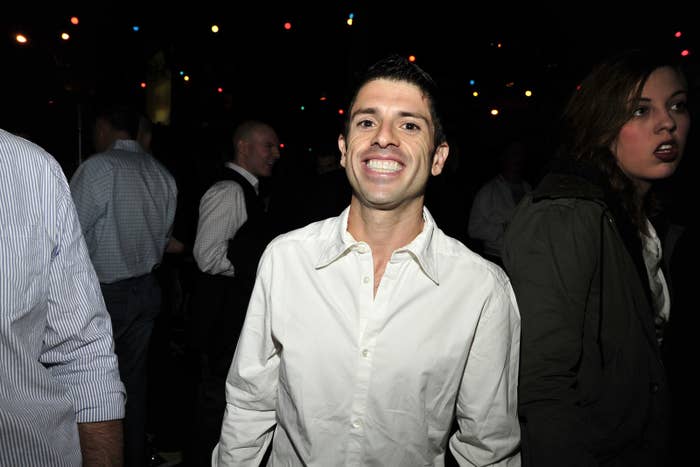

Patrick McMullan via Getty Image

Joel Simkhai attends An Evening at the Bowery Bar at Bowery Bar on March 23, 2010 in New York City.

Connecting Men Who Want to Fuck

Launched in 2009, Grindr was the brainchild of Joel Simkhai, a gay entrepreneur who claimed to have “very little knowledge in terms of technology.” The app addressed a basic human problem — connecting men who wanted to fuck — and its implementation of geolocation with users’ iPhones was a forward-thinking means of helping them solve that. (Grindr debuted on Android in 2011.)

Simkhai maintained control of the company until June 2016, when he sold off a 60% stake to Kunlun for $93 million. After selling the rest to the Chinese social gaming company in January 2018, he was out, with new management reporting to Kunlun headquarters in Beijing. Simkhai did not respond to an interview request for this story.

Little changed at first. Employees still enjoyed their perks, including catered lunches, company-funded parties, and in-office activities like cupcake socials and puppy playdates. At Into, which had launched in August 2017, reporters — most of whom were contractors or freelancers — chased ambitious stories that required travel and video. Meanwhile, the Grindr app was humming, clocking 3.3 million users a day.

At town hall meetings and in interviews, Grindr’s leadership spoke optimistically about the company’s future, which was focused on a more inclusive platform. Despite the app’s success, some executives worried that it wasn’t sustainable and that the company needed to diversify by creating LGBTQ content to diversify beyond hookups and one-night stands.

The first big changes came in February. Grindr’s interim CEO, billionaire Kunlun Chair Yahui Zhou, consolidated some of the company’s operations with those of its Beijing parent. That led to layoffs: first for most of Grindr’s 30 Los Angeles–based engineers and then, in March, another 20 people from sales and marketing. That second wave of layoffs, which included some employees who’d come on just months earlier, became known internally as “the Red Wedding,” a grim reference to a particularly shocking episode of Game of Thrones.

Poor Culture Fits

Four former Grindr employees who spoke to BuzzFeed News traced the beginning of the company’s troubles to two key decisions made during its sale to Kunlun. The first, they said, was Joel Simkhai and Kunlun’s failure to submit the deal for CFIUS review, which at the time of the initial sale in June 2016 was entirely voluntary. Still, the parties involved and their advisers should have taken every precaution to protect the deal, and the Trump administration’s hardline policies against China today only underscore this shortsightedness, one source said.

The second sin was the decision to relocate Grindr’s main engineering operations to Beijing, a move that caused the company to make the personal data of millions of users around the world — including photos, private messages, and HIV status — available to engineers working in a country known for its human rights violations. The CFIUS investigation, which began full bore following the company’s acquisition in January 2018, homed in on the misstep as first reported by Reuters, though no evidence has been found that the data was misused.

A spokesperson for the Treasury Department, whose head chairs CFIUS, said in an email that “the Department does not comment on information relating to specific CFIUS cases.”

While some employees had concerns about sharing data with their Chinese counterparts, their concerns went largely unheard in the leadership vacuum that formed in the company’s West Hollywood headquarters. Former employees said they never saw interim CEO Zhou in their office, leaving Scott Chen, the company’s chief technology officer, as the de facto head of day-to-day operations.

While the CFIUS investigation played out in private, the company faced a public reckoning that spring. In April, BuzzFeed News reported that Grindr, which had 3.6 million daily active users at the time, was sharing its customers’ HIV statuses and other personally identifiable information, including location, phone ID, and email, in nonsecure file formats with third-party companies.

“These are standard practices in the mobile app ecosystem,” Chen told BuzzFeed News in a statement at the time. “No Grindr user information is sold to third parties.”

That response typified Chen’s leadership at the time, said one former employee, who described the report as “a bomb.” Users were outraged that their personal medical data had been shared without their informed consent, senators criticized Grindr, and executives deliberated internally whether the story would further reinforce the impression that the Chinese-owned company was being lax with user data.

Advertising for Into.

Grindr subsequently said it would stop sharing users’ HIV information with third parties, and the furor died down, but the debacle and its fallout showcased its new leadership’s shortcomings. Employees were particularly irked with Chen and what they viewed as his tone-deaf and inappropriate response to a clear violation of user privacy. And his office behavior didn’t help matters.

Multiple former Grindr employees described Chen and his lieutenants, two former Facebook engineers named Alex Lin and Po-chun “Birdy” Chang, as poor cultural fits. While they operated the preeminent app for cis gay males, the three men — all straight — seemed to have little grasp of gay culture. It also didn’t help that they lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, flying to Los Angeles every week for work on the company’s dime.

Through a spokesperson, Chen declined an interview request for this article. Chang declined to speak, while Lin did not respond to a request for comment.

Among the most frustrating things about Chen, according to three former employees, was his seeming lack of interest in anything beyond Grindr’s main app. Although the company had made strides since 2017 to develop a media brand and a wider audience than just gay men, he seemed monomaniacally focused on numbers and was hell-bent on attaining 4 million daily active users.

Former Grindr employees told BuzzFeed News that Chen spent a lot of his time working with the company’s Beijing engineers developing small features and changes to the app that he hoped would drive more engagement, and that he often failed to communicate them to the LA team. Two former employees said Chen also seemed to have little desire to fix the toxicity and harassment problems that plagued the app; he didn’t want to touch things that seemed to be working. “His archaic view of things is that sex sells,” said one, noting that anything that detracted from encouraging hookups was seen as a distraction.

“He thought Into was a social media play and didn’t realize it was an independent news outlet,” one former employee said. Another recalled trying to explain to Chen that media businesses take time to develop audiences and revenue streams and that there would be no quick and easy way to make Into profitable. Chen didn’t seem to listen, they said.

Former Grindr employees said this lack of interest manifested itself in other ways as well, often in decision-making that came off as callous or inappropriate. After a round of layoffs last year, former employees said, Chen removed a cluster of desks in the company’s cavernous office to install his own fitness center. A spokesperson told BuzzFeed News that anyone could use the gym, but two former employees said no one did and it was widely understood to be for his use.

Chen also publicly derided the company’s “Kindr” ad campaign, which sought to combat racism and bullying on the app by sharing stories from different members of the LGBTQ community.

“Scott openly mocked Kindr,” a former employee recalled. “He didn’t understand why we wanted to celebrate what he saw as ‘fat people.’”

Sources said Chen never seemed particularly interested in directly dealing with harassment and abuse and he actively tried to ignore those issues. Three people recalled management deleting more than 500,000 reports — instances in which users flagged content or interactions that potentially violated the company’s terms of service — from Grindr’s internal systems. Reports covered a range of complaints from spam and unsolicited nudes to solicitation and harassment and were ostensibly to be reviewed by third-party moderators.

But during the summer of 2018, Chen and Po-chun Chang decided to switch moderation partners from the company’s India-based provider to Mooley, a Taiwan-based company that had a prior working relationship with Grindr’s parent, Kunlun. At the time, Grindr had amassed an enormous backlog of user reports. Rather then keep them in the moderation queue Chen and Chang opted to simply purge them, two sources in positions to know told BuzzFeed News. These same people said their were at least two mass deletions and both occurred without explanation.

A Grindr spokesperson declined comment on the matter.

“Interested in Chinese Government Relationship”

In the spring of 2018, Chen was among a handful of Grindr executives who knew the company was being investigated by CFIUS. In June, the company hired an Overland Park, Kansas–based data protection officer and global compliance manager who soon advised executives to document their interactions with Beijing.

Three former employees said that Chen didn’t take the threat of the CFIUS inquiry seriously. Having eliminated most of the engineering team in the US while simultaneously looking to diversify from Beijing, Chen started making trips to Taipei, where he eventually opened a 20-person engineering office. Aside from the cheap talent, the Taiwanese office was seen as a way to temper some of the direct scrutiny on Beijing, said two people in positions to know and who understood the move to be motivated by CFIUS.

Although Chen never specifically mentioned to his employees that Grindr was under investigation by the federal government, some deduced that the company was facing an inquest, like one person who was invited to a CFIUS-related meeting they weren’t supposed to attend. Grindr’s president also hired outside consultants, including the Jeb Bush–advised communications firm TrailRunner International, to help, limiting the number of employees who dealt with the issue.

Still, Chen forged ahead, pitching new app features and potential partnerships, some of which were a concern for at least four former employees who heard bits and pieces about the ongoing federal investigation.

July 2018 emails first reported by NBC News showed that Chen sought to build relationships with China’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention by sharing HIV data with a Chinese researcher, despite being aware of the CFIUS inquiry and the earlier privacy concerns around HIV data.

“They are interested in publication and research. They are attracted by our brand, reach and data,” Chen wrote in an email shared with BuzzFeed News to subordinates in early July 2018. “We can’t let people say this is about ‘sharing user data with Chinese government’.”

“For us we are interested in Chinese government relationship and of course, promote sexual health (our [Grindr for Equality] core value),” he added in the note.

In the company’s first statement to BuzzFeed News, a spokesperson for Chen defended his actions by saying that the company and its Grindr for Equality team “periodically engage in discussions with highly respected national and international health organizations and researchers.”

Initially that statement noted that Grindr had never engaged with “any intern associated in any way with the Chinese government.” When BuzzFeed News subsequently notified the company that it had emails showing Chen’s correspondence with the Chinese CDC researcher, Grindr modified its response.

“Regardless of emails you may have regarding a very preliminary internal discussion, Grindr has never engaged an intern or researcher associated in any way with the Chinese government,” a spokesperson said in the new statement.

BuzzFeed News also obtained emails showing that Chen, by September, aimed to build a separate app for users in China, South Korea, and Japan. Pitched as a way to break into the Chinese market and keep China and other Asian customer data in the country, the separate app was immediately flagged by executives because it hadn’t been approved by CFIUS. Many also shared ethical concerns.

“We felt very strongly that doing this would put people there in real danger and that it would be impossible for those users’ data to be safe from the government,” said one former Grindr employee, citing China’s human rights record and persecution of LGBTQ individuals. “To those of us that were gay, that seemed utterly obvious.

“There are just so many anecdotes like this of him being blind to the fact that gay people face real consequences for being who are they are in parts of the world,” they added.

A Grindr spokesperson declined to comment on Chen’s ambitions for the separate Chinese app.

Into the Unknown

Chen officially assumed the role of president in August 2018, the same month Grindr announced its intent to go public. Three people familiar with those plans noted that they were largely driven by Kunlun, which announced the move in a Chinese regulatory filing, unbeknownst to most Grindr employees, who found out by reading the news.

One person familiar with the IPO effort said it had “an impossible timeline from the very beginning.” The company hoped to list within 90 days, an aggressive target that was further complicated by CFIUS, which had ordered Grindr to cut off Beijing-based employees’ access to company databases by September.

That order effectively ended any development that could be done by Chinese engineers. Moreover, employees were told to stop communicating with their Beijing counterparts and to move all company-related communications from WeChat, a popular Chinese messaging platform owned by Tencent, to Slack. Some employees were called into meetings where outside auditors interviewed them about how Grindr handled and secured user data.

A source who spoke to BuzzFeed News said regulatory concerns “accelerated” Grindr’s IPO plans, while three people noted that Chen and executives simultaneously met with investors last summer to pursue alternative options in case a listing wasn’t possible. Investors, both American and foreign, came to meet with the company, with Chen also making trips to Beijing to court other Chinese backers.

Investor meetings, some of which were held in glass conference rooms at the company’s West Hollywood offices, were often disastrous, according to two sources familiar with them. One of these people said that Chen “couldn’t sell Grindr” because he knew nothing about the product or how people used it. Faced with explaining a 10-year-old app’s potential for growth, Chen chose to focus on the company’s hookup past rather than a three-pronged pitch around the main app, Into, and Grindr for Equality that showed Grindr could be a one-stop shop for “everything gay.”

“[Venture capitalists] came in to meet with Scott and they’d walk out shaking their heads,” one source said.

Despite the internal turmoil, Into thrived through the second half of 2018 under the leadership of Editor-in-Chief Zach Stafford and Managing Editor Trish Bendix. While the publication lacked the budget to hire full-time staffers, its editors commissioned ambitious pieces, sending reporters to the migrant caravan in Tijuana to cover LGBTQ issues and to states including Alaska and Massachusetts.

Chen, three people said, didn’t particularly see the value in that. “He saw it as a cost center,” one former employee explained. Stafford, who now hosts BuzzFeed News’ morning show AM2DM, declined to comment. Bendix did not respond to a request for comment.

Then, in late November, Chen posted a note to his personal Facebook page commenting on a vote in Taiwan that legally defined marriage as between a man and a woman.

Screenshot via Facebook

A screenshot of the Facebook post by Chen

“Some people think the marriage is a holy matrimony between a man and a woman,” he wrote. “And I think so too. But that’s your own business.”

The Into story inspired by that remark and the subsequent backlash drove a deep fissure through Grindr. Soon after its publication, Chen, who was traveling for a work trip, wrote a long message in the story’s comments lambasting the piece as “unbalanced and misleading.” He said it had damaged Grindr’s reputation and complained that he had not been asked for comment prior to publication. Communications obtained by BuzzFeed News contradict this statement. (The comments sections on all Into articles have since been removed.)

Meanwhile, some of Grindr’s rank-and-file employees were torn. On the one hand, they were furious with Chen’s comments. On the other, they wondered why Into’s reporters, knowing their president’s lack of experience, hadn’t directly asked him about his views when he was in the office in order to prevent the public controversy. A day after the story, Chen issued a company-wide note stating that his comment was «meant to express my personal feelings about my own marriage to my wife – not to suggest that I am opposed to marriage equality.»

“People were really upset and really mad at Into,” said one employee. “Lost in all of this was this really upsetting moment of, Is the president of Grindr a homophobe?”

In the aftermath, the company’s communications head, Landen Zumwalt, resigned, writing in an open letter that he “refused to compromise [his] own values or professional integrity” to defend Chen’s statements. Grindr’s president would later hold a town hall meeting with Stafford to clear the air and assure writers that no cuts would be made to the publication as a result of the piece.

But the damage was already done. By December, Stafford had left for the Advocate; the following month, Grindr sacked most of Into’s staff and stopped publishing content to its website. The Into brand continues to exist as a YouTube channel for video because “our user base engages and interacts at much higher rates with video than with written pieces,” a company spokesperson told BuzzFeed News.

Internally, the company also spun the move as one made to “rely more heavily on video,” though staffers who had dual positions at both Into and Grindr also lost jobs. Most employees saw the closure as an inevitability finally realized. “Scott had wanted to get rid of Into for a long time,” one former staffer said. “He finally did.”

“I Am Proud of My Work”

By the start of 2019, Grindr was enervated and its employees demoralized as the Into layoffs made an already empty office emptier. In February, the company closed its Beijing office over concerns about handling personal user data as first reported by Reuters. Then, in March, CFIUS officials notified Kunlun that its ownership of Grindr represented a national security threat to the US and that it would have to sell the company by June 2020.

“We were changing strategy against the backdrop of a government investigation,” said one source, who added that CFIUS’s decision killed any prospect of an IPO. “If the government is forcing you to sell your business, you lose public interest and any logical buyer is going to wait until a last-minute fire sale.”

That same person said Grindr had been pitched as a potential acquisition target to dating companies including Tinder owner Match Group and Bumble owner Badoo, to no avail. A spokesperson for Badoo declined comment, while a representative for Match Group did not respond to a request for comment.

The former employees who spoke to BuzzFeed News said they’re unsure where Grindr goes from here. Some have spoken to the FBI, though the authorities they spoke with did not say if their inquiries were for CFIUS or another matter. (The Department of Justice is one of nine CFIUS members.)

Reached by BuzzFeed News, an FBI agent who interviewed former Grindr employees declined to comment on the agency’s work. An FBI spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

“Grindr’s failings are a big loss for the LGBTQ community,” one former employee told BuzzFeed News. “This is a brand that people depend on, and because of myopic decision-making, it’s less effective and not at all what it could be.”

Others remain slightly hopeful, noting that the app, which is profitable and booked more than $50 million in revenue last year, still has a dedicated user base that continues to use the app in spite of its internal failings. Maybe Grindr will find a buyer that will treat it better, they said.

If the last 18 months have done anything for Grindr, they’ve given Chen — who remains president — a crash course in how not to run a business. His personal Facebook page, which caused him and Grindr so much trouble, now has a new introduction.

“I support LGBTQ+ equality, including marriage equality. I am proud of my work at Grindr.”