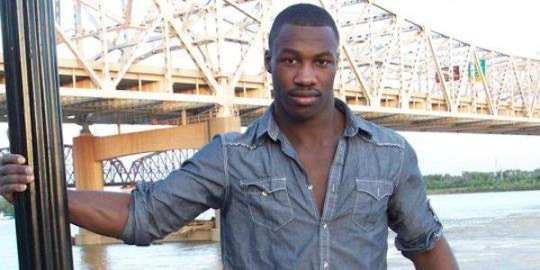

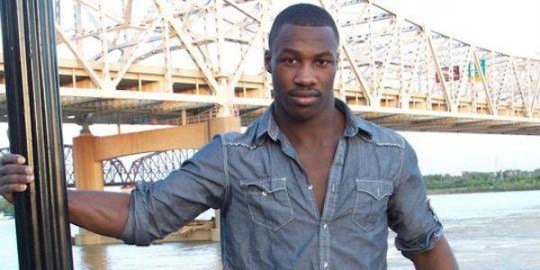

This just in: Michael Johnson (a.k.a. “Tiger Mandingo”), who was unfairly sentenced to 30 years in prison by a homophobic jury for not disclosing his HIV status to his sexual partners, has been released from prison 25 years early.

Just to recap: Johnson was accused of “recklessly infecting” multiple male partners with HIV while he was a student at Lindenwood University in Missouri in 2013.

In 2015, he was sentenced to 30 years by a jury pool stacked with white heterosexuals, the majority of whom admitted that they believed homosexuality was a sin.

The conviction raised questions about America’s HIV criminalization laws, which activists have long said ignore decades of medical science, fail to actually reduce infection rates, and disproportionately punish black men, as HIV rates are higher among people of color.

Both the American Medical Association and the Infectious Diseases Society of America have publicly condemned laws criminalizing HIV.

Nevertheless, Johnson began serving his 30-year sentence in July 2015, spending his entire first year in solitary confinement.

Now, after an appeals court ruled his original trial “fundamentally unfair,” tainted with racism, homophobia, and a prosecuting attorney hellbent on getting a harsher sentence than many murders receive, Johnson has been released from prison.

“I feel great,” he told reporters as he exited the Boonville Correctional Center this morning. “Leaving prison is such a great feeling.”

Timothy Lohmar, the original prosecuting attorney who sought a life sentence for Johnson and who, at one point, threatened him with 96 years imprisonment, has since changed his tune.

He now calls the whole case “embarrassing” and says that he was “forced to operate under the current laws,” which he believes are “antiquated, outdated, and based upon something that science would prove is not accurate.”

Lohmar is now lobbying to get Missouri’s laws around HIV changed.

Currently on the table is HB167, which would reduce the punishment for failing to disclose one’s HIV status from a felony to a misdemeanor. It would also take into account whether a condom was used and if a person was taking medication.

Johnson, who must still serve three years of parole, says that if there’s any good to come from his trial, it’s that the state will update its draconian laws to ensure cases like his never happen again.

“Maybe my trial did happen in some way to motivate some change,” he says.

Reflecting on the outpouring of support he’s received over the last six years, Johnson says, “It’s good I had the support of everyone who wrote me letters. There are times when you get down, and it helps that people knew why I was fighting the system.”