Gay Pride wasn’t born yesterday, but at 50 this month, it’s never been more vital. That’s due, in part, to Rupert Everett, who was something of a pioneer in the movement as it entered adulthood. The 60-year-old actor came out in 1989, five years into his filmography, back when it still was considered certain career suicide to do so.

I’ve always thought of Everett as a successful actor, so I was surprised to come across a 2009 The Guardian profile in which he lamented the effect coming out had had on his career. He also cautioned aspiring gay thespians against making the same mistake: “I would not advise any actor necessarily, if he was really thinking of his career, to come out.”

His rant began with this: “The fact is that you could not be, and still cannot be, a 25-year-old homosexual trying to make it in the British film business or the American film business or even the Italian film business. It just doesn’t work, and you’re going to hit a brick wall at some point.”

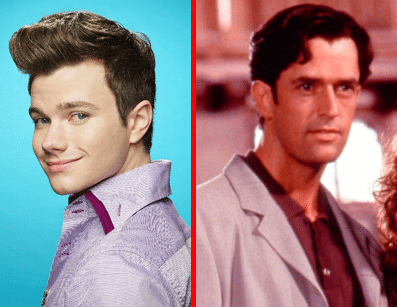

Everett has enjoyed a solid, if not quite spectacular, 35-year career, so it’s tempting to dismiss his gripes as bitterness over its occasionally jagged trajectory, but consider this: If he had come out much later or not at all, would his early promise as the next Cary Grant — or a British Rock Hudson — have translated to eventual superstardom?

Although openly gay actors now can find fairly gainful employment, especially if they look like, say, Matt Bomer, and can be mistaken for straight, we still don’t have one of Will Smith’s or Bradley Cooper’s A-list caliber.

No openly gay actor has ever won a performing Oscar (Kevin Spacey, Sir John Gielgud, and Cabaret’s Joel Grey were not publicly out when they grabbed their gold), and even bisexual and sexually/gender fluid ones hit that brick wall. Nico Tortorella has publicly identified as all three, and that might partly explain why he has yet to parlay his exposure on Younger and his leading-man good looks into substantial TV roles.

It’s harder to answer that definitively than it is to blame Everett’s Oscar snub for playing Will to Julia Roberts’ Grace in the 1997 hit My Best Friend’s Wedding on an Academy that’s more likely to be floored by a straight actor negotiating a gay character with such finesse (see Rami Malek’s and Mahershala Ali’s 2019 wins — and even Olivia Colman’s). Did the Academy pass over him despite his receiving rave reviews and Golden Globe and BAFTA nominations because voters assumed he was just playing himself?

We’ll never know for sure, but by choosing the courageous road less taken, Everett may have instantly pigeonholed himself. That’s something any fledgling gay actor should consider. While there are benefits to being out from the start — never having to worry about the dreaded tabloid expose, for one — there are potential hazards.

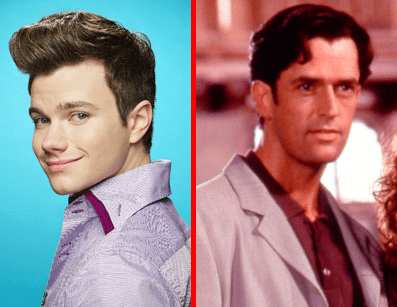

If you claim stardom as a gay character, you run the risk of being typecast. This is particularly true if you don’t fit the “bro”-gay standard. Chris Colfer won a Golden Globe as the openly gay Kurt Hummel on Glee, but according to Wikipedia, most of his post-Glee TV credits have been playing himself — literally.

Four-time Emmy winner David Hyde Pierce never hid his sexual orientation, but he probably owes his longevity to staying quiet about it for so long. Had he been out of the closet during Frasier’s heyday, would viewers have been as invested in Niles’s romance with Daphne?

Like Pierce, Neil Patrick Harris, Matt Bomer, Zachary Quinto, and Ben Whishaw, all waited until they were fairly established before coming out as gay, which might have been wise of them. Harris probably wouldn’t have been cast as the womanizing Barney Stinson on How I Met Your Mother if he had outed himself 10 years earlier than he did. That the show’s popularity didn’t suffer after he came out in 2006, though, shows that Hollywood underestimates the viewing public’s capacity to suspend disbelief.

Quinto has worked steadily since coming out in 2011, but his profile is considerably lower than that of his straight Star Trek costar Chris Pine. Meanwhile, Whishaw has won rave reviews, a Golden Globe and a BAFTA for playing Hugh Grant’s lover in the 2018 TV miniseries A Very English Scandal, but the onetime frontrunner for the role of Freddie Mercury in Bohemian Rhapsody watched the part (and the Oscar) go to the more marketing-friendly (i.e., straight) Rami Malek.

Speaking of Mercury, music wasn’t particularly hospitable to gay and bisexual men when the late Queen frontman was alive or even for decades after he died. Coming out didn’t hurt the professional standing of Elton John in 1976, George Michael in the early ’90s, or Ricky Martin in 2010, but all three were already well-established by that time. Had they not been, Elton’s 1970-76 commercial peak, Michael’s Grammy-winning Faith, and Martin’s “Livin’ la Vida Loca” might never have happened.

The times, they are a-changing in music, though. Adam Lambert, Sam Smith, and Troye Sivan were out pretty much from the start, and all three have done well anyway. Then there is Frank Ocean, whose success still begs unavoidable questions: Did Channel Orange, his 2012 debut album, sell 131,000 copies in the U.S. during its first week because of the publicity surrounding his pre-release admission that his first love had been a man? Or did it sell that many in spite of it?

Was Ocean more acceptable because he resisted labeling himself as gay or bisexual, and veers far from the stereotypical campy gay man? I wonder how fans and the hip-hop community would have reacted had he come out and said, “I’m gay,” then showed up on a red carpet holding a man’s hand the week of the album’s release. Would Channel Orange still have done as well as it did?

At least the music industry occasionally bows down to gay pride. Hollywood merely curtsies politely. The movies still treat straight actors playing gay with far more respect. Until filmmakers respond to our gay pride with more gay pride of their own, the likes of Rami Malek and Mahershala Ali will continue to reap all the greatest benefits of living our lives.