Jerry Mitchell with his Tony Award

Jerry Mitchell with his Tony Award

Sirens sound as I pick up the phone.

“Sorry, I’m on the New York street.”

Jerry Mitchell apologizes for the noise.

The out-gay Tony Award-winning director and choreographer of shows like Hairspray, Legally Blonde and Dirty Rotten Scoundrels sounds a bit out of breath. We don’t need to ask why.

In addition to having just wrapped the annual benefit Broadway Bares, a burlesque review that raises money for HIV/AIDS research, just the week before, Mitchell is unveiling his cinematic production of Kinky Boots at Frameline, the San Francisco-based queer media arts foundation.

Based on the film of the same name, Kinky Boots follows the parallel lives of Charlie, heir to a shoe factory and Simon, an aspiring drag queen. With the factory on the edge of bankruptcy, Charlie enlists Lola–Charlie’s drag persona–to help design a new line of shoes which will revitalize the business.

With a score by Cyndi Lauper and a book by Harvey Fierstein, Kinky Boots became a Broadway smash running for more than 2,500 performances and winning six Tony Awards, including best choreography for Mitchell, and best actor for a then-unknown Billy Porter. The show helped catapult Porter to leading man status, and cemented Mitchell’s name as one of the biggest on Broadway.

The filmed version of Kinky Boots comes from the West End production, and stars original London leads Killian Donnelly and Matt Henry. It lands in select cinemas nationwide this June 25 and 29.

Queerty scored a few minutes with Mitchell to talk about bringing the show to the big screen, and his career on the wicked stage.

Once Harvey and Cyndi had signed off on it, it was all about how do we get it together and make it happen? We got the original two leads back who opened in the West End, Killian Donnelly and Matt Henry, both of whom were off doing other things. Matt won the Olivier for his performance. And we went to town. We did it for a week. We got them back in the show and put it together over four or five days. It was great fun. Everybody had a ball doing it.

It is tricky, and you’ve gotta know who you’re working with. The folks at Steam [Steam Motion and Sound, which filmed the show], I was a big fan of theirs. I was very impressed with their work. We’d done Legally Blonde for MTV. I had done that with Hairspray: LIVE for NBC. So I came to it with a little bit of experience about how to take a Broadway show in the theatre and try and get that on the screen. I think it came off well. I did see the finished edit and I was very happy with where we were.

For me, you know what? I wasn’t part of that decision. I had to go where they sent me. But, you know, I think there’s still room for a Kinky Boots film, a proper full musical film of it. I’m hopeful that could happen someday, and I might be involved with it. I think Harvey wants it to happen. I think Cyndi wants it to happen. Who knows? There’s still room.

Here’s how I work, and here’s how I think it works best. I’ve been under, as a performer, as a dancer—don’t forget, I was in A Chorus Line—which was done all over the world. I worked for Jerry Robbins [director of West Side Story]. I worked for Michael Bennett [director of Dreamgirls]. I watched them do this with their productions, sometimes really well, sometimes not as well. What I’ve learned is that the show, sets, costumes, lights—the static things will always be the same. What will never be the same is an actors interpretation of the role. My job as a director is to get all of the actors in every company I put together all on the same page, working together as a company, telling the story their way. I never ask an actor to do something that another actor did in terms of making a choice about how to play a scene or read a line. Yes, they have to do the choreography, they have to stand where the light comes on or where it goes off, but even that I change sometimes. And I always change for the place we’re playing. We made a lot of changes in London. We made a lot of changes in Korea. We made a lot of changes in Japan, things that would help their culture understand our story. That’s important. If you close your eyes to that, you do put up a stale production.

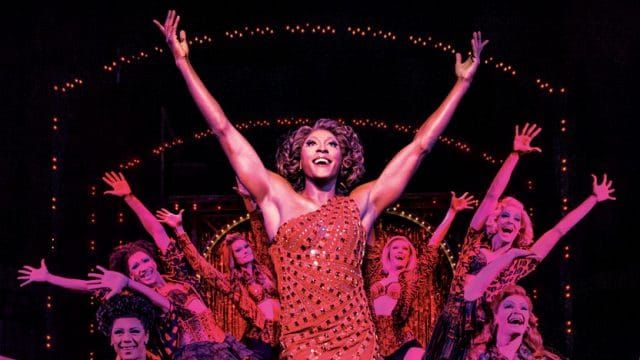

Matt Henry as Simon/Lola

Matt Henry as Simon/Lola

Here’s another way to put it: When you hire a group of actors, you’re asking them to invest in the story. How can they invest if they don’t put in a deposit? If they don’t go to the bank and make a deposit, what will they have to draw on when they have to do it eight times a week six months into the run? So you have to, as a director, get a cast to invest in the story. The only way to do that is to invite them to be creative with you.

Absolutely. You have to start over. That’s even harder, because the actor who’s been doing the show and doesn’t leave has been working with one actor, and has to be open to rehearsing with a new actor and finding new things. That’s kind of what keeps it alive for everybody. Look at Kinky Boots: we had so many different guys come in and play Lola/Simon. Wayne Brady, Todrick Hall, J. Harrison Ghee—every time they came in, because the template was set by Billy and everyone in the production about welcoming them and being there to support them, we never had that kind of a problem.

Yeah.

Yeah.

I think that’s one of the reasons the show was so successful.

Absolutely. I think they became brothers. And I think that relationship is more powerful than a love relationship for men on a lot of levels. There are so many men who are straight who love gay men and are friends with them and have no fear in that. There are so many others that do have fear that a gay man can never be friends with a straight man because it will always be about sex. I think that’s one thing that makes the show so strong.

Never. Not once. Harvey was really, when we first started talking, Harvey locked into an idea that he wanted it to be about two guys not living up to the expectations of their fathers and finding out that even though they were from opposite ends of the Earth, they share the same relationship with their fathers: basically being failures in their father’s eyes. So they first had to learn to succeed and to accept themselves, so they could heal that relationship. That was the whole arc of what we were attempting to do.

Here’s the deal. I choreographed Cyndi 25 years ago for the closing ceremony of the gay games. It was the first time I worked with her. She came to me and said “I want to do “Hey Now” with 50 drag queens.” I said, “Oh my God, incredible. Let’s do it.” So we put the number together, and it was so much fun, she said she wanted to make a video with it. So we made a video. Michael Musto was in drag in it, and in the video.

We had that relationship. She did Broadway Bares for me. Harvey I go back to Hairspray with, La Cage, Broadway Bares, so we had a really great relationship. So there was no intimidation because we all joined together to want to do this story, and we’d all worked together. So it was effortless. And Billy Porter, I hired when he was 19 to be in one of the first musicals I ever directed.

He got the job but didn’t take it because he wanted to finish school. Then I hired him to be in Grease with Jeff Calhoon. Then we were friends all the way up to when this happened. And I said, “Billy, this is the role.” And he said, “I know.” I said, “Come read it.” And that was it. We never looked at anyone else.

Yeah.

For most of them, it was a producer coming to me and asking me if I thought it would make a good musical. There have been a lot of others, some that made it to Broadway that I thought there’s no way. But these—I tried to get the rights to Hairspray and to Kinky Boots at one point. So these were two stories that I was really passionate about.

When I came to Broadway in 1980, the AIDS crisis was hitting New York City. I always think of dance as a naturally sexual form of expression, of storytelling. You use a physical body to do it. If you think about it, in the 80s, there was no choreography. There were no shows with choreography because everyone was afraid to relate to each other physically.

It started to come back in the 90s. That’s when Broadway musicals started to pick up again after the devastating loss of the 80s. Dance became another way of expressing musical theatre, which had been lost. So because there weren’t writers, producers were looking for material to adapt, so of course, they went to film since they don’t read books anymore.

[Laughter]

It’s faster to watch a 2-hour film than it is to read a book. So that’s what was getting offered to me. What’s ironic is my next two musicals I’m working on are both incredible stories. The first is called Becoming Nancy, and it’s about a young boy in the musical Oliver! who gets cast as Nancy and falls in love with the boy who gets cast as Bill Sykes in 1979. It’s such a beautiful story. The one after that is called Drag King, with Jeffery Phelps, Steven Arena, Jake Shears and myself adapting a book. So my next two musicals are adapted from books and both deal with gay characters. I’m really excited. They’re both great.

We premiere Becoming Nancy September 4 at The Alliance in Atlanta. Then hopefully Broadway next spring. It’s really special.

Everyone here was dead, dying or flying to France to get AZT. That’s what was happening.

That’s my take on it. Musicals at that time still cost $5-10 million and there was nobody with a track record to stake that on. It was a very scary time on Broadway.

My partner is actually in St. Louis right now doing Kinky Boots. He comes back Wednesday. His birthday is July 6. We have a house out in The Pines [on Fire Island]. We’re having Pride in the Pines with a bunch of friends.

Oh, I have some Trump stories.

Yeah, I did Will Rodgers Follies with Marla Maples [Trump’s mistress and briefly, his second wife]. I have all sorts of Wife #2 stories.

Kinky Boots streams into select theatres June 25 & 29.