According to Guest Curator Vincent Honoré, “Kiss My Genders is a wonderful celebration welcoming the brilliant differences and the rich spectra of genders within our society.”

Here we speak to Honoré about the purpose and potential of Kiss My Genders, before finding out what inspired Jenkin van Zyl, the exhibition’s youngest artist, to fly to Morocco’s Atlas Mountains to make a “kaleidoscopic horror” film that’s gut-punchingly powerful.

Vincent Honoré.

A few weeks into the exhibition’s three-month run, I call Honoré, who’s based in Paris, to hear his take on why Kiss My Genders is so vital. “I think this exhibition is timely because on the one hand the diversity of genders is becoming more visible in the streets, online and in our mainstream media,” he says. “But on the other hand, there’s this counter-effect that manifests in a rise in homophobia and transphobia that we can see almost every day in the newspaper. So in that sense, this exhibition is politically timely. But it’s also formally timely because there’s an exciting emerging generation of artists who are inspired by the history of queer art, but at the same time creating new forms and new aesthetics. I’m thinking in this exhibition of [artists like] Flo Brooks, Jenkin van Zyl and Jes Fan, for instance.”

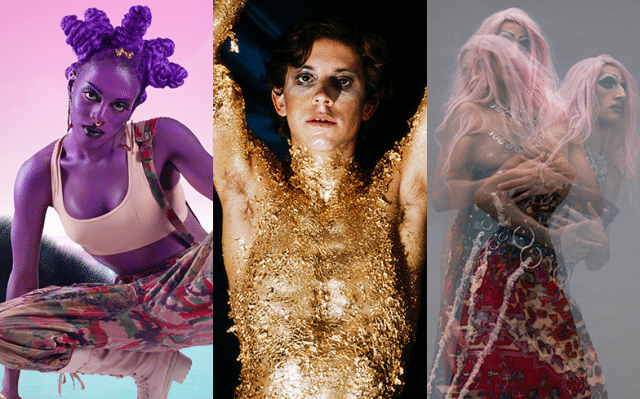

Kiss My Genders takes over the gallery’s two spacious floors and seems to offer something playful, thought-provoking and inspirational at every turn. Commenting on the way that marginalised groups are “forced to be their own saints”, black trans writer-artist-performer Juliana Huxtable creates imagery that portrays her as iconic mythological creatures. Collaborating with photographer Holly Falconer, writer-performer-filmmaker Amrou Al-Kadhi poses for a triple exposed photograph “to help relay the schizophrenic experience of being in drag as a person of Muslim heritage”. An immersive video installation by Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings explores two very different queer spaces in Blackpool: gloriously camp drag showbar Funny Girls and sexually-charged men-only club Growlr. It’s an impressively varied collection of works created by a thrillingly queer palette of artists. As Honoré notes matter-of-factly, “there isn’t a single cis heterosexual artist in this exhibition”.

The curator says he wanted Kiss My Genders to contain “a broad range of mediums including paintings, installations and videos”, and also to feel like a “living organism”. “It was important to me that we weren’t just showing pictures on the wall, that we were also creating conversations around the exhibition,” he explains. To that end, Kiss My Genders includes several talks and panel events, a late session from DJ-producer Honey Dijon, and innovative musical shows from Peaches and Planningtorock. The exhibition’s title is taken from the latter’s song Transome, a celebration of their genderqueer identity on which they sing: “Baby, you touch me right / Kissing my genders in our bedroom light.”

Actually, the importance of celebrating different gender identities could be the exhibition’s core message. “I think this is the first exhibition in a massive art gallery in the UK which isn’t just [about] addressing queer theories, but trying to go beyond that and create a real celebration of different genders,” Honoré says. “This exhibition addresses a lot of pain, but also a lot of joy in terms of being oneself. Numerous artists [in the exhibition] said to me that they didn’t want for their work to be attached to any more exhibitions that simply address pain; they want to be known for addressing joy as well. They also said that they wanted to be part of an exhibition that really celebrates differences.” Though he’s pleased with the positive feedback he’s received from critics, audience members and the artists themselves, Honoré also says that Kiss My Genders was a “problematic” and “impossible” exhibition to curate. How so? “It’s because we are working with deep and violent emotions. When someone is deciding and exploring his or her or their own identity, those are very violent emotions,” he explains. “So all of the artists are working with their own emotions, but all of the audience members are going to have different emotional reactions to their works as well. Though we have a very diverse range of artists in this exhibition, some people could still feel as though they’re not represented.”

This difficulty was compounded, Honoré thinks, because Kiss My Genders is the first exhibition of its kind. “We don’t have a history of these exhibitions yet. I hope that in a few years’ time, we will have that history, and I hope that other curators will take different angles from the one we’ve taken,” he adds.

But ideally, what does he want audience members to take away from Kiss My Genders? “I want it to a very intense experience for the audience – aesthetically pleasant, but also an intellectual journey and an emotional journey in which we reflect on our culture and realise that genitals are not what defines human beings. And in terms of the artists, I would be happy if Kiss My Genders could give the emerging ones other opportunities to produce and share their works and have them shown in galleries. I don’t want these artists to be pigeonholed as “queer artists”. There are so many talented artists out there working [in the areas of] queer theories and aesthetics, but I hope that at some point we can go beyond that kind of limited classification.”

And somewhat paradoxically, perhaps, Honore hopes that by celebrating differences, Kiss My Genders can bring people together. “I hope that by visiting this exhibition people will see that there’s no ‘us’ and ‘other’. I hope that they’ll see we’re all here living in this community of differences, and we can create a way of life by being together.”

Jenkin van Zyl.

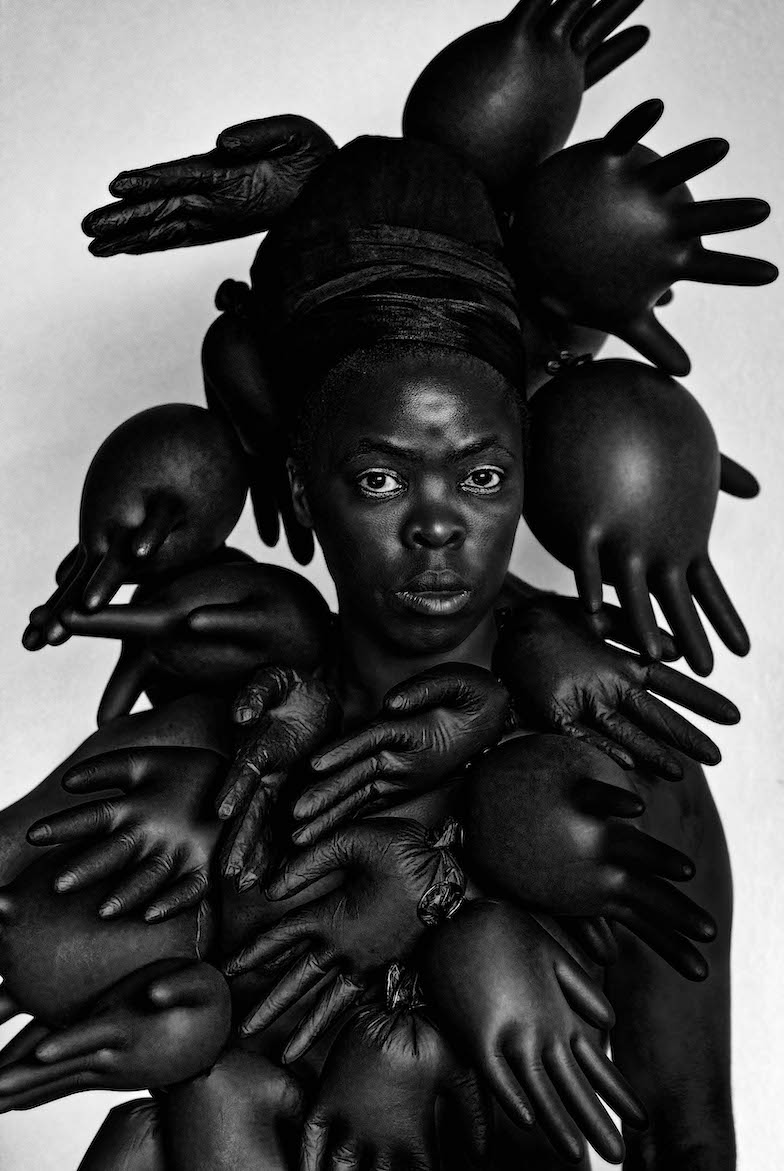

Curator Vincent Honoré says he wanted Kiss My Genders to “look at gender from a very contemporary, emerging artist point of view”, so Jenkin van Zyl was a natural fit. At 25 years old, he’s the youngest artist in the exhibition and midway through a three-year course at London’s Royal Academy of Arts. He’s also fiercely ambitious and frighteningly talented. Many audience members will come across – and be confronted by – his “kaleidoscopic fantasy” film Looners towards the end of the exhibition, when they enter the bespoke cinema room it’s screened in. Inside, distressed wooden floorboards and decorative weaponry create an ambiguous yet unsettling environment for van Zyl’s 30-minute film to cast its dark spell. Shot on disused Hollywood film sets in Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, Looners takes place in a world where a gang of masked, semi-human creatures enact grisly rituals in pursuit of “a kind of love-as-violence, and violence-aslove”. It’s a freaky, bloody and (in both senses) gutsy send-up of macho movie violence that stays with you long after you leave the gallery. Here, the artist deconstructs what it’s all about.

How would you describe Looners to someone who hasn’t seen it yet?

Looners is a kaleidoscopic fantasy filmed in the immense ruins of Hollywood film sets in the Atlas Mountains, primarily in a fortress used for Game of Thrones. Kept here are an unruly species somewhere between human and monster, who seek out re-enchantment through a death drive of hazing.

Looners uses multiple video screens to create a viewing experience that feels immersive and visual. What kind of an effect do you think it will have on people?

Looners is at its core a horror film, and I think that at its best horror can desolidify and redistribute ideas of the self, allowing an emancipatory pleasure in the wake of its ability to obliterate. It thinks about the simultaneous terror and joy of being torn apart, and then tries to bring the audience [with it] into a series of these quantum leaps into mayhem. I intensify this through sculptural escapees and environment that wonkily spills out like a funhouse mirror of the film.

How is Looners concerned with gender identity?

Queer culture has always been the compulsory yet optimistic laboratory for the construction of new heretical sexualities, and in my work I’m always trying to create spaces of potentiality. But it’s also bittersweet – ultimately I’m left thinking about gender as being fundamentally painful, with male and female both being unsatisfying and oppressive, and so Looners treats gender as a terrifying maelstrom. The film immerses itself inside tropes of masculinist cinematic violence in order to tease out a subversion of their ghosts.

What’s the significance of the silicone masks that your performers wear?

I’m trying to destabilise ideas of identity. This, and the pressure point where ideas of the original and the copy collapse, is encouraged in my films through the masked performer. During filming these silicone masks start to act as springboards for improvisation, anonymising performers into a species of nearly-human/almost monstrous genders.

You’re the youngest artist in the exhibition. In what ways are you inspired by queer art from the recent past?

Someone who has really shaped some of the thinking of queer politics in the film is [American musician and public speaker] Terre Thaemlitz. I also feel indebted to the performance methodologies from [German artist] Anne Imhoff and [American artist-filmmaker] Ryan Trecartin and endless intense phone calls with my friend and artist Alex Margo Arden. Ultimately Looners is a tribute to the gang of queens I perform and film with in the work, and my hope would be that some of the weird joy and playfulness from its making could be infectious.