Director Gregor Schmidinger

Director Gregor Schmidinger

The hour has grown late in Vienna, Austria when we finally get Gregor Schmidinger on the phone.

He’s called Austria home for most of his life, save the time he spent studying film at UCLA. Since returning to his native land, Schmidinger has already earned notice for his first film Homophobia, as well as for several other queer-themed shorts. This July 19, he returns to Los Angeles with his latest film, the surreal drama Nevrland.

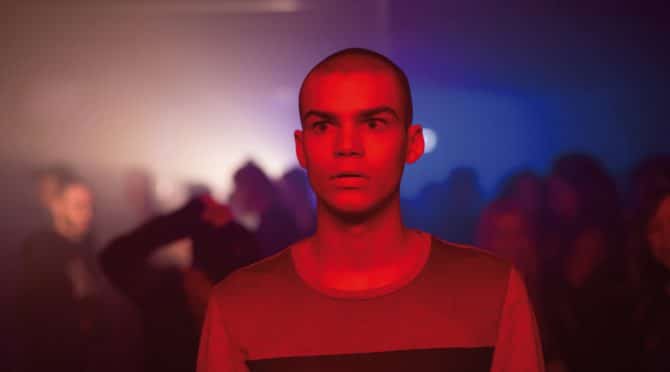

The film follows 17-year-old Jakob (newcomer Simon Frühwirth), a closeted gay teen living with his emotionally distant father (Josef Hader) and catatonic grandfather, and forced to work in a local pig slaughterhouse. As Jakob struggles with mounting anxiety and depression, he makes a connection with Kristjan (Paul Forman), an American photographer via a webcam chat site. When Jakob finally seeks out Kirstjan at a local rave, he enters a dark and erotic journey into his own subconscious where he must face his deepest impulses, and his darkest fears.

Nevrland wowed us with its hallucinatory imagery, sexual charge and tender observations about loneliness. We managed to chat with Schmidinger about the film just before he returned to Los Angeles. Nevrland plays at Outfest July 19.

With post-gay, the idea was to make a queer film where queerness or, in this case, being gay, is not the issue or a problem. So we have a gay character, but his sexual identity or sexual orientation is not the main theme, like coming out stories or homophobia or things like that. Those things are important, but since I touched on them with my last film Homophobia, I wanted to take that next step and deal with different issues that I do feel are very much important with the LGBTQ community, in this case, mental health and anxiety.

Paul Forman (left) with Simon Frühwirth

Paul Forman (left) with Simon Frühwirth

It’s been a long journey, a journey of four years writing the screenplay. The first draft was completely different from the final film. There’s a lot of myself in Jakob, so for example, I was suffering from severe anxiety disorder for most of my 20s. That was a huge part that went into the film, and for me, was an opportunity to deal with that topic from a more artistic point of view than from a very personal, therapeutic point of view. I’ve noticed that a lot of people actually have to deal with panic and anxiety disorders, and I do feel that it gets worse in a way. So it encouraged me to explore that and make that the main theme in a way. And as I said, it was a journey of four years. The first draft was my final project at UCLA where I studied screenwriting. Then, my artistic mentor Markus Schleinzer, a screenwriter-director in Austria helped me find my voice in a way. The first draft was far more what you’d expect in a coming-of-age film compared to what it is now, which is way darker and more psychological. The films that I like are darker, more psychological films, so that was an opportunity to combine two genres in a way.

Yeah. The idea was that the main source of his anxiety and is need for comfort has to do with the backstory of his mother leaving him. For me—and I discussed this with my story consultant, and she’s someone very keen on providing an equal perspective of male and female in a film—we decided to go a very radical way of basically not showing any women within the experiential horizon of Jakob. So the only time you become aware of a female presence is through voice. For example, when he listens to his autogenic training in his room. These were opportunities for me to show or make perceivable what’s missing in his life. And yeah, it made things harder for him. Empathy and compassion are what he’s missing the most within his life. That’s what he has to learn in a way—to have compassion for himself.

It was also an opportunity to discover male archetypes, like the grandfather who is, more or less, the fallen tyrant. Or the father who is a rather tragic figure. We talked a lot about it with the actor [Josef Hader], because we didn’t want him portrayed as a bad person. He just does not know how to talk to his son. He doesn’t understand anything about the universe. It’s a tragic situation they’re all trapped in. They try to make the best of it, which everyone explores in their own addictions, whether its porn, or TV or folk music.

Yes, though I have not seen much of his work.

For me, what I learned when I was dealing with my anxiety disorder, is that your body becomes your worst enemy in a way because anxiety is something that arises as a physical sensation in the body that is very uncomfortable. In the end, Nevrland for me is a journey back into the body which is a source of pleasure and pain at the same time. They are basically two sides of one coin. That was a way of exploring the physicality of the body. What I also learned in my journey of conquering anxiety was that the breath becomes a key element that connects the mind with the body. That’s also why the last words spoken in the film are “Just breathe.” That was trying to connect the mind and the body in a way that they are equally important in experiencing life.

It’s interesting too, my father was a butcher. My first draft, Jakob was working in a bookstore. So that’s completely different from what it is now. During the development process, I figured I could make it harder for the character if I made him work in a slaughterhouse, because there he is confronted with everything he’s trying to escape in himself. So that’s an autobiographical reference in there I suppose.

Lynch was influential in a way in that I like how he can create this dreamlike stasis where you’re not quite sure what’s real and what’s not. There’s this uneasiness I guess. Another big influence was Gasper Noe, the French director of Enter the Void. He also makes use of strobe lights and neon lights. Another influence, certainly—one film specifically that kept coming up during preproduction was Eyes Wide Shut.

For one, it’s an adaptation of a very famous Viennese novel, which also deals with this in-between state of reality and dreams. So that became an influence: following a character through different spaces and exploring those spaces with the character. For a long time David Fincher was an influence, aesthetically. Fight Club was one of my favorite films for a very long time, so like the doppelganger motif, things like that found their way into Nevrland as well.

Yes.

It used to be taboo for a very long time. I think slowly, it’s become a public discussion. But we’re still very uneducated, I guess. For my parents’ generation, it was like depression did not exist, and anxiety is something that you just suck it up in a way. So I guess it’s not so different from the US. I do feel at least that within my bubble, it has come up in recent years. It is a big social issue which becomes worse the more the world becomes insecure politically, or the more we communicate through media, especially social media. So I’d guess it will be an important topic in the future, and one to face head-on.

I guess that was also [inspiration] for a line in the film “Whatever you’re running away from, turn around and look it in the eye and you may realize it isn’t the big, scary thing you think it is.”

It was more a way to become sure that the way I designed the characters and their relationships worked. It was more to verify what I already intuitively had in mind at that point. But it was very interesting. I think there were some parts of the father and grandfather, some details of their relationships that weren’t clear at that point. But it more verified what we already had.

Well what we did was, since Simon, who plays Jakob—this was his first acting experience, ever. He never did anything before this, not even school theatre.

And with a film set you have 20 people standing around. So what we did was before shooting we did some workshops for choreography. We call them intimacy workshops. Simon and Paul had a chance to get comfortable with one another physically. We did a series of exercises where they would say colors like green, which meant “fine,” yellow which meant “uncomfortable,” and red which was a no-go. So they found how they could interact physically with one another so that nobody gets into an uncomfortable situation.

Then, on set itself, we staged everything very precisely before shooting so everyone knew what was going to happen. Everyone was fine with it. We also talked about what’s ok to be seen on screen. We had a couple of screenshots from other films so they could say “Ok, I can see myself doing that,” or “That’s not fine.” And I took that very seriously.

It was a closed set, so it was a very familiar, very intimate situation to shoot. We had a lot of fun, and it didn’t feel like work most of the time.

One very pragmatic reason is that I feel it’s easier for me to write images than dialogue.

[Laughter]

Dialogue doesn’t come easy to me. And that ties in with the whole concept. Jakob’s mind is first and foremost a place of images, less of words. Words are very specific and conscious in a way. I think it also becomes almost hypnotic at a point. Words make everything clean in a way. [With images] you get sucked in, in a way. It was more of an intuitive process. I didn’t realize until someone pointed out at the world premiere that for the first 15-20 minutes nobody speaks. I wasn’t aware of that.

Simon Frühwirth (right) with Josef Hader

Simon Frühwirth (right) with Josef Hader

Not sure yet. There are a few ideas I’m testing right now, but nothing I can say. There’s definitely my attempt to take the thematic world of Nevrland and do something with it for my next project without it being a sequel. But nothing I can specify.

Nevrland plays July 19 at Outfest. It comes to theatres in the US this fall.